The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Unione (“the North”) and the Confederacy (“the South”), which had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union.

The central conflict leading to the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which many believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.16

Decades of political controversy over slavery were brought to a head by the victory in the 1860 U.S. presidential election of Abraham Lincoln, who opposed slavery’s expansion into the western territories. Seven southern slave states responded to Lincoln’s victory by seceding from the United States and forming the Confederacy. The Confederacy seized U.S. forts and other federal assets within their borders. The war began when on April 12, 1861, Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor. A wave of enthusiasm for war swept over both North and South, as recruitment soared. The states in the undecided border region had to choose sides, although Kentucky declared it was neutral. Four more southern states seceded after the war began and, led by Confederate President Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy asserted control over about a third of the U.S. population in eleven states. Four years of intense combat, mostly in the South, ensued.

During 1861–1862 in the Western Theater, the Union made significant permanent gains—though in the Eastern Theater the conflict was inconclusive. The abolition of slavery became a Union war goal on January 1, 1863, when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared all slaves in rebel states to be free, which applied to more than 3.5 million of the 4 million enslaved people in the country. To the west, the Union first destroyed the Confederacy’s river navy by the summer of 1862, then much of its western armies, and seized New Orleans. The successful 1863 Union siege of Vicksburg split the Confederacy in two at the Mississippi River, while Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s incursion north failed at the Battle of Gettysburg. Western successes led to General Ulysses S. Grant’s command of all Union armies in 1864. Inflicting an ever-tightening naval blockade of Confederate ports, the Union marshaled resources and manpower to attack the Confederacy from all directions. This led to the fall of Atlanta in 1864 to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, followed by his March to the Sea. The last significant battles raged around the ten-month Siege of Petersburg, gateway to the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Confederates abandoned Richmond, and on April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant following the Battle of Appomattox Court House, setting in motion the end of the war. Lincoln lived to see this victory but on April 14, he was assassinated.

Appomattox is often referred to symbolically as the end of the war, although arguably there are several different dates for the war’s conclusion. Lee’s surrender to Grant set off a wave of Confederate surrenders—the last military department of the Confederacy, the Department of the Trans-Mississippi disbanded on May 26. By the end of the war, much of the South’s infrastructure was destroyed. The Confederacy collapsed, slavery was abolished, and four million enslaved black people were freed. The war-torn nation then entered the Reconstruction era in an attempt to rebuild the country, bring the former Confederate states back into the United States, and grant civil rights to freed slaves.

The Civil War is one of the most extensively studied and written about episodes in U.S. history. It remains the subject of cultural and historiographical debate. The myth of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy is often the subject of critical analysis. The American Civil War was among the first wars to use industrial warfare. Railroads, the telegraph, steamships, the ironclad warship, and mass-produced weapons were all widely used during the war. In total, the war left between 620,000 and 750,000 soldiers dead, along with an undetermined number of civilian casualties, making the Civil War the deadliest military conflict in American history.f The technology and brutality of the Civil War foreshadowed the coming World Wars.

Causes of secession

Main articles: Origins of the American Civil War and Timeline of events leading to the American Civil War

Status of the states, 1861

Slave states that seceded before April 15, 1861

Slave states that seceded after April 15, 1861

Border Southern states that permitted slavery but did not secede (both KY and MO had dual competing Confederate and Unionist governments)

Union states that banned slavery

Territories

The reasons for the Southern states’ decisions to secede have been historically controversial, but most scholars today identify preserving slavery as the central reason for their decision to secede.17 Several of the seceding states’ secession documents designate slavery as a motive for their departure.16 Although some scholars have offered additional reasons for the war,18 slavery was the central source of escalating political tensions in the 1850s.19 The Republican Party was determined to prevent any spread of slavery to the territories, which, after they were admitted as free states, would give the free states greater representation in Congress and the Electoral College. Many Southern leaders had threatened secession if the Republican candidate, Lincoln, won the 1860 election. After Lincoln won, many Southern leaders felt that disunion was their only option, fearing that the loss of representation would hamper their ability to enact pro-slavery laws and policies.20 21 In his second inaugural address, Lincoln said that:

slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.22

Slavery

Main article: Slavery in the United States

Disagreements among states about the future of slavery were the main cause of disunion and the war that followed.23 24 Slavery had been controversial during the framing of the Constitution in 1787, which, because of compromises, ended up with proslavery and antislavery features.25 The issue of slavery had confounded the nation since its inception and increasingly separated the United States into a slaveholding South and a free North. The issue was exacerbated by the rapid territorial expansion of the country, which repeatedly brought to the fore the question of whether new territory should be slaveholding or free. The issue had dominated politics for decades leading up to the war. Key attempts to resolve the matter included the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850, but these only postponed the showdown over slavery that would lead to the Civil War.26

The motivations of the average person were not necessarily those of their faction;27 28 some Northern soldiers were indifferent on the subject of slavery, but a general pattern can be established.29 As the war dragged on, more and more Unionists came to support the abolition of slavery, whether on moral grounds or as a means to cripple the Confederacy.30 Confederate soldiers fought the war primarily to protect a Southern society of which slavery was an integral part.31 32 Opponents of slavery considered slavery an anachronistic evil incompatible with republicanism. The strategy of the anti-slavery forces was containment—to stop the expansion of slavery and thereby put it on a path to ultimate extinction.33 The slaveholding interests in the South denounced this strategy as infringing upon their constitutional rights.34 With large percentages of their populations in slavery, southern whites saw abolition as inconceivable and believed that the emancipation of slaves would destroy southern families, society, and the South’s economy, with large amounts of capital invested in slaves and longstanding fears of a free black population.35 In particular, many Southerners feared a repeat of the 1804 Haitian massacre (referred to at the time as “the horrors of Santo Domingo”),36 37 in which former slaves systematically murdered most of what was left of the country’s white population after the successful slave revolt in Haiti. Historian Thomas Fleming points to the historical phrase “a disease in the public mind” used by critics of this idea and proposes it contributed to the segregation in the Jim Crow era following emancipation.38 These fears were exacerbated by the 1859 attempt by John Brown to instigate an armed slave rebellion in the South.39

Abolitionists

Main article: Abolitionism in the United States

The abolitionists—those advocating the end of slavery—were active in the decades leading up to the Civil War. They traced their philosophical roots back to some of the Puritans, who believed that slavery was morally wrong. One of the early Puritan writings on this subject was The Selling of Joseph, by Samuel Sewall in 1700. In it, Sewall condemned slavery and the slave trade and refuted many of the era’s typical justifications for slavery.40 41

The American Revolution and the cause of liberty added tremendous impetus to the abolitionist cause. Even in Southern states, laws were changed to limit slavery and facilitate manumission. The amount of indentured servitude dropped dramatically throughout the country. An Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves sailed through Congress with little opposition. President Thomas Jefferson supported it, and it went into effect on January 1, 1808, which was the first day that the Constitution (Article I, section 9, clause 1) permitted Congress to prohibit the importation of slaves. Benjamin Franklin and James Madison each helped found manumission societies. Influenced by the American Revolution, many slave owners freed their slaves, but some, such as George Washington, did so only in their wills. The number of free black people as a proportion of the black population in the upper South increased from less than one percent to nearly 10 percent between 1790 and 1810 as a result of these actions.42 43 44 45 46 47

The establishment of the Northwest Territory as “free soil”—no slavery—by Manasseh Cutler and Rufus Putnam (who both came from Puritan New England) would also prove crucial. This territory (which became the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota) virtually doubled the size of the United States. If those states had been slave states and voted for Abraham Lincoln’s chief opponent in 1860, Lincoln would not have become president.48 49 41

Frederick Douglass, a former slave, was a leading abolitionist

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, abolitionists, such as Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Frederick Douglass, repeatedly used the Puritan heritage of the country to bolster their cause. The most radical anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, invoked the Puritans and Puritan values over a thousand times. Parker, in urging New England congressmen to support the abolition of slavery, wrote, “The son of the Puritan … is sent to Congress to stand up for Truth and Right.”50 51 Literature served as a means to spread the message to common folks. Key works included Twelve Years a Slave, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, American Slavery as It Is, and the most important: Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the best-selling book of the 19th century aside from the Bible.52 53 54

A more unusual abolitionist than those named above was Hinton Rowan Helper, whose 1857 book, The Impending Crisis of the South: How to Meet It, “[e]ven more perhaps than Uncle Tom’s Cabin … fed the fires of sectional controversy leading up to the Civil War.”55 A Southerner and a virulent racist, Helper was nevertheless an abolitionist because he believed, and showed with statistics, that slavery “impeded the progress and prosperity of the South, … dwindled our commerce, and other similar pursuits, into the most contemptible insignificance; sunk a large majority of our people in galling poverty and ignorance, … [and] entailed upon us a humiliating dependence on the Free States…“56

By 1840 more than 15,000 people were members of abolitionist societies in the United States. Abolitionism in the United States became a popular expression of moralism, and led directly to the Civil War. In churches, conventions and newspapers, reformers promoted an absolute and immediate rejection of slavery.57 58 Support for abolition among the religious was not universal though. As the war approached, even the main denominations split along political lines, forming rival Southern and Northern churches. For example, in 1845 the Baptists split into the Northern Baptists and Southern Baptists over the issue of slavery.59 60

Abolitionist sentiment was not strictly religious or moral in origin. The Whig Party became increasingly opposed to slavery because it saw it as inherently against the ideals of capitalism and the free market. Whig leader William H. Seward (who would serve as Lincoln’s secretary of state) proclaimed that there was an “irrepressible conflict” between slavery and free labor, and that slavery had left the South backward and undeveloped.61 As the Whig party dissolved in the 1850s, the mantle of abolition fell to its newly formed successor, the Republican Party.62

Territorial crisis

Further information: Slave states and free states

Manifest destiny heightened the conflict over slavery. Each new territory acquired had to face the thorny question of whether to allow or disallow the “peculiar institution”.63 Between 1803 and 1854, the United States achieved a vast expansion of territory through purchase, negotiation, and conquest. At first, the new states carved out of these territories entering the union were apportioned equally between slave and free states. Pro- and anti-slavery forces collided over the territories west of the Mississippi River.64

The Mexican–American War and its aftermath was a key territorial event in the leadup to the war.65 As the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo finalized the conquest of northern Mexico west to California in 1848, slaveholding interests looked forward to expanding into these lands and perhaps Cuba and Central America as well.66 67 Prophetically, Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that “Mexico will poison us”, referring to the ensuing divisions around whether the newly conquered lands would end up slave or free.68 Northern free-soil interests vigorously sought to curtail any further expansion of slave territory. The Compromise of 1850 over California balanced a free-soil state with a stronger federal fugitive slave law for a political settlement after four years of strife in the 1840s. But the states admitted following California were all free: Minnesota (1858), Oregon (1859), and Kansas (1861). In the Southern states, the question of the territorial expansion of slavery westward again became explosive.69 Both the South and the North drew the same conclusion: “The power to decide the question of slavery for the territories was the power to determine the future of slavery itself.”70 71 Soon after the Utah Territory legalized slavery in 1852, the Utah War of 1857 saw Mormon settlers in the Utah territory fighting the US government.72 73

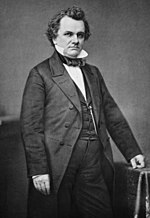

Sen. Stephen A. Douglas, author of the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854

Sen. John J. Crittenden, of the 1860 Crittenden Compromise

By 1860, four doctrines had emerged to answer the question of federal control in the territories, and they all claimed they were sanctioned by the Constitution, implicitly or explicitly.74 The first of these theories, represented by the Constitutional Union Party, argued that the Missouri Compromise apportionment of territory north for free soil and south for slavery should become a constitutional mandate. The failed Crittenden Compromise of 1860 was an expression of this view.75

The second doctrine of congressional preeminence was championed by Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party. It insisted that the Constitution did not bind legislators to a policy of balance—that slavery could be excluded in a territory, as it was in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, at the discretion of Congress.76 Thus Congress could restrict human bondage, but never establish it. The ill-fated Wilmot Proviso announced this position in 1846.77 The Proviso was a pivotal moment in national politics, as it was the first time slavery had become a major congressional issue based on sectionalism, instead of party lines. Its support by Northern Democrats and Whigs, and opposition by Southerners, was a dark omen of coming divisions.78

Senator Stephen A. Douglas proclaimed the third doctrine: territorial or “popular” sovereignty, which asserted that the settlers in a territory had the same rights as states in the Union to allow or disallow slavery as a purely local matter.79 The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 legislated this doctrine.80 In the Kansas Territory, political conflict spawned “Bleeding Kansas”, a five-year paramilitary conflict between pro- and anti-slavery supporters. The U.S. House of Representatives voted to admit Kansas as a free state in early 1860, but its admission did not pass the Senate until January 1861, after the departure of Southern senators.81

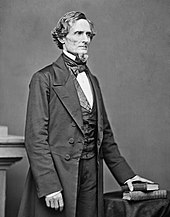

The fourth doctrine was advocated by Mississippi Senator (and soon to be Confederate President) Jefferson Davis.82 It was one of state sovereignty (“states’ rights”),83 also known as the “Calhoun doctrine”,84 named after the South Carolinian political theorist and statesman John C. Calhoun.85 Rejecting the arguments for federal authority or self-government, state sovereignty would empower states to promote the expansion of slavery as part of the federal union under the U.S. Constitution.86 These four doctrines comprised the dominant ideologies presented to the American public on the matters of slavery, the territories, and the U.S. Constitution before the 1860 presidential election.87

States’ rights

A long-running dispute over the origin of the Civil War is to what extent states’ rights triggered the conflict. The consensus among historians is that the Civil War was not fought about states’ rights.88 89 90 91 But the issue is frequently referenced in popular accounts of the war and has much traction among Southerners. Southerners advocating secession argued that just as each state had decided to join the Union, a state had the right to secede—leave the Union—at any time. Northerners (including pro-slavery President Buchanan) rejected that notion as opposed to the will of the Founding Fathers, who said they were setting up a perpetual union.92

Historian James McPherson points out that even if Confederates genuinely fought over states’ rights, it boiled down to states’ right to slavery.91 McPherson writes concerning states’ rights and other non-slavery explanations:

While one or more of these interpretations remain popular among the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other Southern heritage groups, few professional historians now subscribe to them. Of all these interpretations, the states’-rights argument is perhaps the weakest. It fails to ask the question, states’ rights for what purpose? States’ rights, or sovereignty, was always more a means than an end, an instrument to achieve a certain goal more than a principle.91

States’ rights was an ideology formulated and applied as a means of advancing slave state interests through federal authority.93 As historian Thomas L. Krannawitter points out, the “Southern demand for federal slave protection represented a demand for an unprecedented expansion of Federal power.”94 95 Before the Civil War, slavery advocates supported the use of federal powers to enforce and extend slavery, as with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the Dred Scott v. Sandford decision.96 97 The faction that pushed for secession often infringed on states’ rights. Because of the overrepresentation of pro-slavery factions in the federal government, many Northerners, even non-abolitionists, feared the Slave Power conspiracy.96 97 Some Northern states resisted the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. Historian Eric Foner states that the act “could hardly have been designed to arouse greater opposition in the North. It overrode numerous state and local laws and legal procedures and ‘commanded’ individual citizens to assist, when called upon, in capturing runaways.” He continues, “It certainly did not reveal, on the part of slaveholders, sensitivity to states’ rights.”89 According to historian Paul Finkelman, “the southern states mostly complained that the northern states were asserting their states’ rights and that the national government was not powerful enough to counter these northern claims.”90 The Confederate Constitution also “federally” required slavery to be legal in all Confederate states and claimed territories.88 98

Sectionalism

Ambrotype of two unidentified young boys, one in blue Union cap, one in gray Confederate cap (Liljenquist collection, Library of Congress)

Sectionalism resulted from the different economies, social structure, customs, and political values of the North and South.99 100 Regional tensions came to a head during the War of 1812, resulting in the Hartford Convention, which manifested Northern dissatisfaction with a foreign trade embargo that affected the industrial North disproportionately, the Three-Fifths Compromise, dilution of Northern power by new states, and a succession of Southern presidents. Sectionalism increased steadily between 1800 and 1860 as the North, which phased slavery out of existence, industrialized, urbanized, and built prosperous farms, while the deep South concentrated on plantation agriculture based on slave labor, together with subsistence agriculture for poor whites. In the 1840s and 1850s, the issue of accepting slavery (in the guise of rejecting slave-owning bishops and missionaries) split the nation’s largest religious denominations (the Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches) into separate Northern and Southern denominations.101

Historians have debated whether economic differences between the mainly industrial North and the mainly agricultural South helped cause the war. Most historians now disagree with the economic determinism of historian Charles A. Beard in the 1920s, and emphasize that Northern and Southern economies were largely complementary. While socially different, the sections economically benefited each other.102 103

Protectionism

Owners of slaves preferred low-cost manual labor and free trade, while Northern manufacturing interests supported mechanized labor along with tariffs and protectionism.104 The Democrats in Congress, controlled by Southerners, wrote the tariff laws in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, and kept reducing rates so that the 1857 rates were the lowest since 1816. The Republicans called for an increase in tariffs in the 1860 election. These increases were enacted in 1861, after Southerners resigned their seats in Congress.105 106 The tariff issue was a Northern grievance, but neo-Confederate writers have claimed it was a Southern grievance. In 1860–61 none of the groups that proposed compromises to head off secession raised the tariff issue.107 Pamphleteers from the North and the South rarely mentioned the tariff.108

Nationalism and honor

Nationalism was a powerful force in the early 19th century, with famous spokesmen such as Andrew Jackson and Daniel Webster. While practically all Northerners supported the Union, Southerners were split between those loyal to the entirety of the United States (called “Southern Unionists”) and those loyal primarily to the Southern region and then the Confederacy.109

Perceived insults to Southern collective honor included the enormous popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and abolitionist John Brown’s attempt to incite a slave rebellion in 1859.110 111

While the South moved towards a Southern nationalism, leaders in the North were also becoming more nationally minded, and they rejected any notion of splitting the Union. The Republican national electoral platform of 1860 warned that Republicans regarded disunion as treason and would not tolerate it.112 The South ignored the warnings; Southerners did not realize how ardently the North would fight to hold the Union together.113

Lincoln’s election

Main article: 1860 United States presidential election

Mathew Brady’s Portrait of Abraham Lincoln, 1860

The election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 was the final trigger for secession.114 Southern leaders feared that Lincoln would stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction.115 However, Lincoln would not be inaugurated until five months after the election, which gave the South time to secede and prepare for war in the winter and spring of 1861.116

According to Lincoln, the American people had shown that they had been successful in establishing and administering a republic, but a third challenge faced the nation: maintaining a republic based on the people’s vote, in the face of an attempt to destroy it.117

Outbreak of the war

Secession crisis

The election of Lincoln provoked the legislature of South Carolina to call a state convention to consider secession. Before the war, South Carolina did more than any other Southern state to advance the notion that a state had the right to nullify federal laws, and even to secede from the United States. The convention unanimously voted to secede on December 20, 1860, and adopted a secession declaration. It argued for states’ rights for slave owners in the South but complained about states’ rights in the North in the form of opposition to the federal Fugitive Slave Act, claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their obligations under the act to assist in the return of fugitive slaves. The “cotton states” of Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas followed suit, seceding in January and February 1861.118

Among the ordinances of secession passed by the individual states, those of three—Texas, Alabama, and Virginia—specifically mentioned the plight of the “slaveholding states” at the hands of Northern abolitionists. The rest make no mention of the slavery issue and are often brief announcements of the dissolution of ties by the legislatures.119 However, at least four states—South Carolina,120 Mississippi,121 Georgia,122 and Texas123 —also passed lengthy and detailed explanations of their reasons for secession, all of which laid the blame squarely on the movement to abolish slavery and that movement’s influence over the politics of the Northern states. The Southern states believed slaveholding was a constitutional right because of the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution. These states agreed to form a new federal government, the Confederate States of America, on February 4, 1861.124 They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries with little resistance from outgoing President James Buchanan, whose term ended on March 4, 1861. Buchanan said that the Dred Scott decision was proof that the South had no reason for secession, and that the Union “was intended to be perpetual”, but that “The power by force of arms to compel a State to remain in the Union” was not among the “enumerated powers granted to Congress”.125 One-quarter of the U.S. Army—the entire garrison in Texas—was surrendered in February 1861 to state forces by its commanding general, David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy.126

As Southerners resigned their seats in the Senate and the House, Republicans were able to pass projects that had been blocked by Southern senators before the war. These included the Morrill Tariff, land grant colleges (the Morrill Act), a Homestead Act, a transcontinental railroad (the Pacific Railroad Acts),127 the National Bank Act, the authorization of United States Notes by the Legal Tender Act of 1862, and the ending of slavery in the District of Columbia. The Revenue Act of 1861 introduced the income tax to help finance the war.128

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America (1861–1865)

In December 1860, the Crittenden Compromise was proposed to re-establish the Missouri Compromise line by constitutionally banning slavery in territories to the north of the line while permitting it to the south. The adoption of this compromise likely would have prevented the secession of the Southern states, but Lincoln and the Republicans rejected it.129 Lincoln stated that any compromise that would extend slavery would in time bring down the Union.130 A pre-war February Peace Conference of 1861 met in Washington, proposing a solution similar to that of the Crittenden Compromise; it was rejected by Congress. The Republicans proposed the Corwin Amendment, an alternative compromise not to interfere with slavery where it existed, but the South regarded it as insufficient. Nonetheless, the remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy following a two-to-one no-vote in Virginia’s First Secessionist Convention on April 4, 1861.131

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as president. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and called any secession “legally void”.132 He had no intent to invade Southern states, nor did he intend to end slavery where it existed, but said that he would use force to maintain possession of federal property,132 including forts, arsenals, mints, and customhouses that had been seized by the Southern states.133 The government would make no move to recover post offices, and if resisted, mail delivery would end at state lines. Where popular conditions did not allow peaceful enforcement of federal law, U.S. marshals and judges would be withdrawn. No mention was made of bullion lost from U.S. mints in Louisiana, Georgia, and North Carolina. He stated that it would be U.S. policy to only collect import duties at its ports; there could be no serious injury to the South to justify the armed revolution during his administration. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union, famously calling on “the mystic chords of memory” binding the two regions.132

The Davis government of the new Confederacy sent three delegates to Washington to negotiate a peace treaty with the United States of America. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents because he claimed the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government.134 Lincoln instead attempted to negotiate directly with the governors of individual seceded states, whose administrations he continued to recognize.135

Complicating Lincoln’s attempts to defuse the crisis were the actions of the new Secretary of State, William Seward. Seward had been Lincoln’s main rival for the Republican presidential nomination. Shocked and embittered by this defeat, Seward agreed to support Lincoln’s candidacy only after he was guaranteed the executive office that was considered at that time to be the most powerful and important after the presidency itself. Even in the early stages of Lincoln’s presidency Seward still held little regard for the new chief executive due to his perceived inexperience, and therefore Seward viewed himself as the de facto head of government or “prime minister” behind the throne of Lincoln. In this role, Seward attempted to engage in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed.134 However, President Lincoln was determined to hold all remaining Union-occupied forts in the Confederacy: Fort Monroe in Virginia, Fort Pickens, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Taylor in Florida, and Fort Sumter in South Carolina.136